top of page

PORTFOLIO

INSTALLATIONS

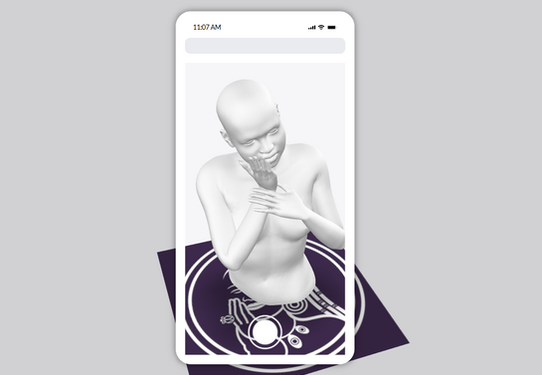

Sacred Remains

The work was presented during the panel discussion, exhibition, and workshop series titled Art, Science and the Deceased Body: Towards a Duty of Care, held from 13–16 May 2025, in South Africa. The event was hosted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal in collaboration with the KwaZulu-Natal Museum.

Introduction

This work emerged as a personal and conceptual meditation on memory, loss, and the digital traces we leave behind.

“Sacred Remains” explores the intersection of technology and the human body, using digital reconstruction to create a modern equivalent of Byzantine iconography. Both systems of representation rely on mediated presence, symbolic representation, and a belief in the power of the image to connect the viewer with something beyond the material. But where the Byzantine icon was shaped by faith, this digital icon is shaped by data, by what remains in the cloud rather than in scripture. It invites the viewer not to worship, but to witness, to reflect on how technology now assumes the role of sanctifying memory, turning digital traces into sites of veneration.

Conceptual Framework

Sacred Remains reflects on how, in a digital age, memory and presence persist through data.

In the past, physical spaces and objects preserved our past. Now, much of it is stored in the cloud, rendered in 3D, or lived out in online environments. Data preservation in virtual spaces opens up intriguing questions about memory, identity, and even the nature of reality. The way data is stored in these virtual spaces and the role it plays in shaping our collective memory and individual experience are a reflection of how we interact with technology today.

Virtual spaces enable idealized identities.

Another important aspect is the way we present ourselves online. It often reflects a curated, polished image that may not fully capture the complexity or authenticity of our lives. This creates a kind of "virtual memory" that is not just a collection of events, but rather a selective and often exaggerated version of who we are. This raises some interesting questions about the tension between reality and representation in digital spaces. How do these idealized memories shape our perceptions of ourselves and others? Are we losing touch with more authentic experiences, or is this idealization a form of self-empowerment, a way to control our narrative in a world full of chaos? Virtual spaces enable not just idealized identities, but also the creation of multiple, fragmented personas, which could be a metaphor for our evolving understanding of self in the digital age.

AI, 3D Modeling and AR

One of the pragmatic aspects of digital practice is the fact that information can be infinitely developed, recycled, and reproduced in various contexts – it can breed new ideas through recombination. The recontextualization of information in various relational combinations is inherently connected to the logic of the database, which ultimately lies at the core of any digital art project. As media theorist Lev Manovich has put it, a digital art object can be described as one or more interfaces to a database of multimedia material. Manovich’s definition points to the fact that the virtual object is bound to the concept of an interface that allows the user or viewer to experience it.

In Sacred Remains, AI functions as an interface – a system through which the digital traces of a lost friend – photos, messages, metadata – are accessed, interpreted, and transformed into a visual form. AI is the keeper of this collective memory, capable of drawing connections between different traces and reassembling them into a coherent, evocative form. Through this collaboration, the artist engages AI as both translator and medium: it translates the raw data of memory into the shape of a digital sculpture, while the artist guides this process, shaping the outcome through intentional design and emotional insight. The resulting digital work is not just a representation of the deceased, but a manifestation of how memory persists and can be reanimated through technology. In this sense, the interface becomes sacred – a site where loss, remembrance, and digital presence converge.

Interaction and Installation Mechanics

-

Viewer scans QR code.

-

Marker triggers the appearance of a 3D body.

-

AR sculpture arises from digital remains.

The work is not ‘on display’ in a traditional sense – It must be summoned. It exists conditionally, like memory itself.

Conclusion

The act of digital reconstruction draws a deliberate parallel to Byzantine iconography, where the human figure was idealized not for realism, but to express spiritual truth and transcendence. In a similar way, Sacred Remains does not attempt to replicate the deceased realistically, but to evoke a sense of sacred presence through abstraction, light, and form. Just as icons served as intermediaries between the earthly and the divine – windows into a higher reality – this digital sculpture, accessed through augmented reality, becomes a contemporary icon: a portal into the preserved digital essence of a life once lived.

Both traditions rely on mediated presence, symbolic representation, and a belief in the power of the image to connect the viewer with something beyond the material. But where the Byzantine icon was shaped by faith, this digital icon is shaped by data, by what remains in the cloud rather than in scripture. It invites the viewer not to worship, but to witness, to reflect on how technology now assumes the role of sanctifying memory, turning digital traces into sites of veneration.

Big Man

Yane Bakreski, Michelle Stewart, Peter Stewart

24th International Symposium on Electronic Art, ISEA2018

Durban Art Gallery, June 25-30, 2018, Durban, South Africa

Photographs by Christo Doherty

There is no question that this installation, in its scale, its mode of address, and its content, asked profoundly poignant political questions, in this case, about the meaning of personal power and the effects of political corruption on the lives of ordinary South Africans. It was also one of the most compelling works in the "Other Realities" program, using a powerful design and making effective use of technology which drew large audience who stood beneath the screens of the installation, attracted by the complex patterning of looped video images across the multiple screens and the striking subject matter.

Prof. Christo Doherty

Deputy Director of School: Art Research, The Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

The installation was a valuable contribution to the curated exhibition at the Durban Art Gallery and the broader cultural program of ISEA2018. Not only in its conceptual technical presentation in line with the technology focus of the works on show but with the strong locally relevant statement around corruption of power, both in the South African and international context. This artwork was a successful fit with the ISEA2018 subthemes and overall curatorial intention of both the exhibition and the discourse of digital art as locally relevant investigation and statement. In this way the work presents a worthy creative output for the research and development of this local artistic discipline and discourse.

Marcus Neustetter

Artistic Director - ISEA2018 Durban, Director: The Trinity Session

Augmented Abstraction

24th International Symposium on Electronic Art, ISEA2018

Durban Art Gallery, June 25-30, 2018, Durban, South Africa

Photographs by Christo Doherty

The subject of the installation is inter-spatiality in art. The critical challenge is to detach color (sensations) from form (representation) and make the creative process aboveboard, i.e., deal openly with the audience. “Augmented Abstraction” deals with creating a simple Augmented Reality (AR) system designed to create an immersive environment a computer simulates. Consisting of a camera, a computational unit, and a display, the system is run on a tablet PC using a built-in camera. Using marker-based tracking, it captures the marker, which is digitally painted nude, depicted in a mode of everyday visibility, and displayed on a large TV screen. The augmentation is in 3D, consisting of multiple parallel offset planes (parallel to the marker), holding the Photoshop layers, i.e., different abstract color patches, color patterns, brushstrokes, etc., produced during the nude painting process, thus creating complex 3D abstract permutations. By using AR technology, the final result is a chance to simultaneously observe the real world, represented in the mode of everyday visibility, and the virtual elements that exemplify the idea or the abstract code.

Augmented Abstraction

Ohrid Summer Festival, 2016

University of Information Science and Technology "St. Paul the Apostle" Ohrid, Macedonia

bottom of page